When Apple launched the App Store in 2008, there were only a handful of apps on there.

A few months later?

Countless, high-quality apps published by countless developers.

But why did that happen? And how?

From a 2023 perspective, it would be easy to make the mistake of thinking, “well, it’s Apple! The biggest company in the world. Everyone has an iPhone, so you’d be crazy not to publish something on the App Store…”

But thinking that the App Store grew because of Apple’s distribution capacity is wrong. At the time, not many people had an iPhone!

The reason the App Store exploded in popularity came down to one key thing:

Incentives i.e. stimuli or motivators used to encourage or promote specific behaviours or actions.

Specifically, Apple introduced a 70-30 revenue split with developers. This means that for every dollar earned by an app, Apple would take 30 cents, leaving 70 cents for the developer. This monetisation strategy created an incentive for ambitious developers to commit their time & resources to building an app specifically for Apple’s App Store.

And because of that incentive, we saw the explosion in new app innovation that continues to this day.

Incentives Go Both Ways

As product leaders, clearly we want to create positive incentives i.e. to encourage specific behaviour or actions that serve a business purpose (such as more valuable apps for users & more revenue from those apps in the case of Apple).

However, we must also be wary of creating negative incentives i.e. unintended, negatives outcomes caused by specific behaviours or actions we encourage.

A great example of this comes from Colonial India:

Under British rule, the government was concerned about the number of venomous cobra snakes in Delhi.

To reduce the population, they offered a bounty for every dead cobra. Initially, it worked, and many snakes were killed for the reward. However, some enterprising individuals began breeding cobras to claim more bounties.

When the government became aware of this and canceled the program, the breeders released their worthless snakes, leading to an even larger cobra population than before the reward was offered.

The term "Cobra Effect" now refers to a situation where an incentive produces the opposite outcome of what was intended.

How To Understand Incentives When Building Product

Whether we like to admit it or not, every change we make - every decision about which revenue model or which new feature to introduce - will affect our customers’ behaviour and actions.

Whether that be positive or negative for us as a business is what we need to try to consider when making those decisions.

And this is particularly important for us as product leaders. It’s a common mistake to think of incentives as design decisions - relegated to the realm of UX & not a priority. As you’ll see in the examples below, in many cases, engineering certain incentives forms the core product strategy - and determines the success or failure of a product (as in the case of TripAdvisor or Peak in the examples below)

Here are 4 types of incentives to help guide you towards better decisions:

Financial Incentives: Essentially, any monetary reward we give out for achieving a specific target or goal.

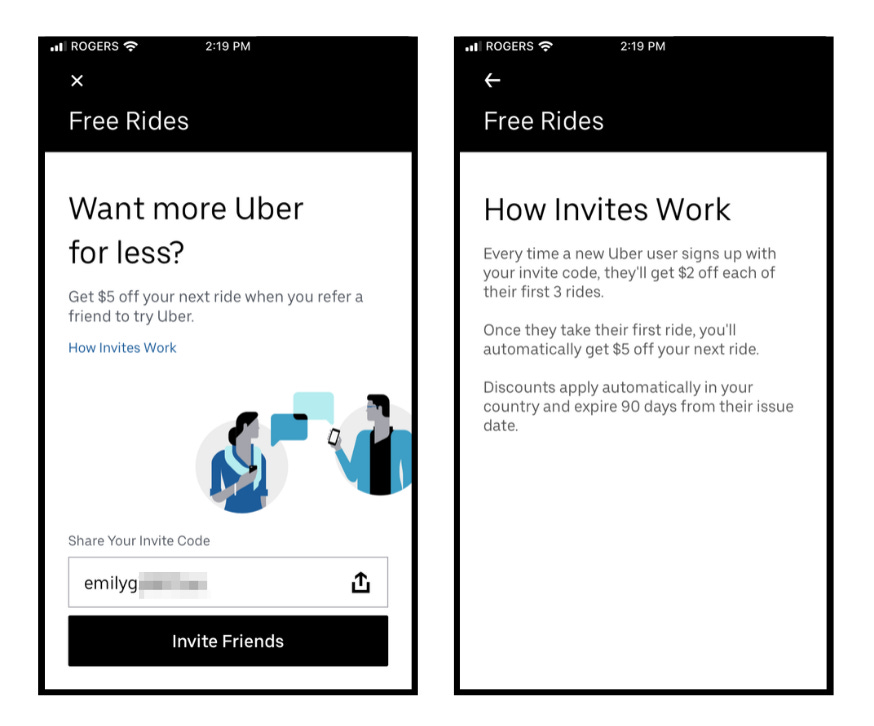

For example, we might increase acquisition of new customers through a paid referral programme, like Uber.

However, we want to be careful about how we structure financial incentives. For example, what if that referral programme brings in the wrong kind of user? Or what if users learn how to “game” our referral programme by creating fake accounts? These kind of potential negative incentives need to be considered (and this is precisely why, if we look at Uber’s referral programme below, the user only receives their $5 bonus once the invitee actually pays for a first ride).Or we may bake financial incentives into our pricing strategy.

A great example of this is Amazon Prime:By introducing a subscription pricing model, Amazon Prime has created an incentive for customers to make more frequent purchases. Why? Because they enjoy unlimited free shipping. Therefore, why wait to order a few items in one go to avoid delivery fees when delivery fees no longer exist?

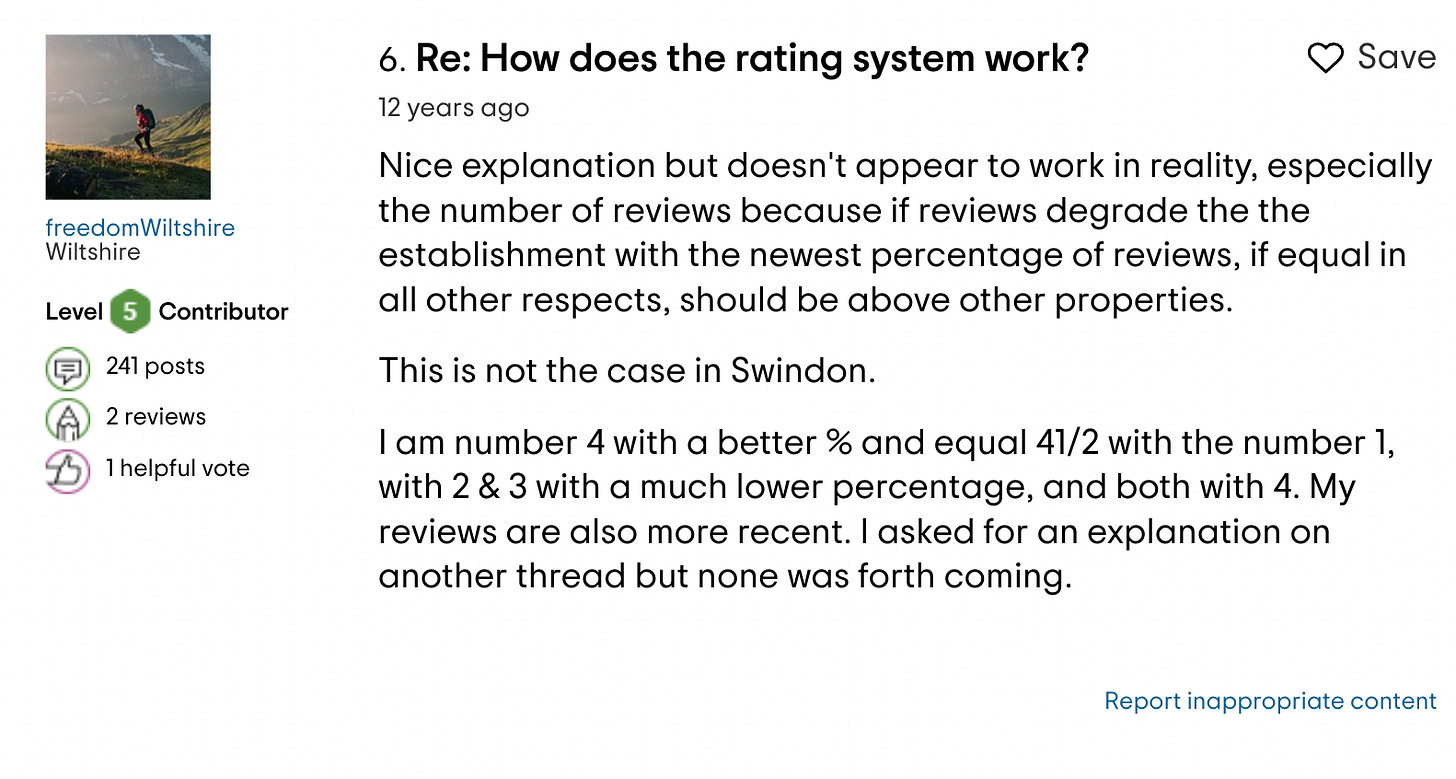

Non-Financial Incentives: These incentives are not linked directly to monetary rewards. They can include recognition, career progression opportunities, learning and development resources, flexible work hours, and more. TripAdvisor provides a great example of how recognition can power product outcomes (see below). By creating different levels for contributors, they provide social recognition for users. Therefore, the more a user contributes, the more recognition they get, providing more useful, engaging content for all of its users

Intrinsic Incentives: These are the internal rewards or satisfaction a person gets from performing a particular task or job. Intrinsic incentives can include the satisfaction of doing meaningful work, the thrill of a challenge, the joy of learning something new, or a sense of personal growth.

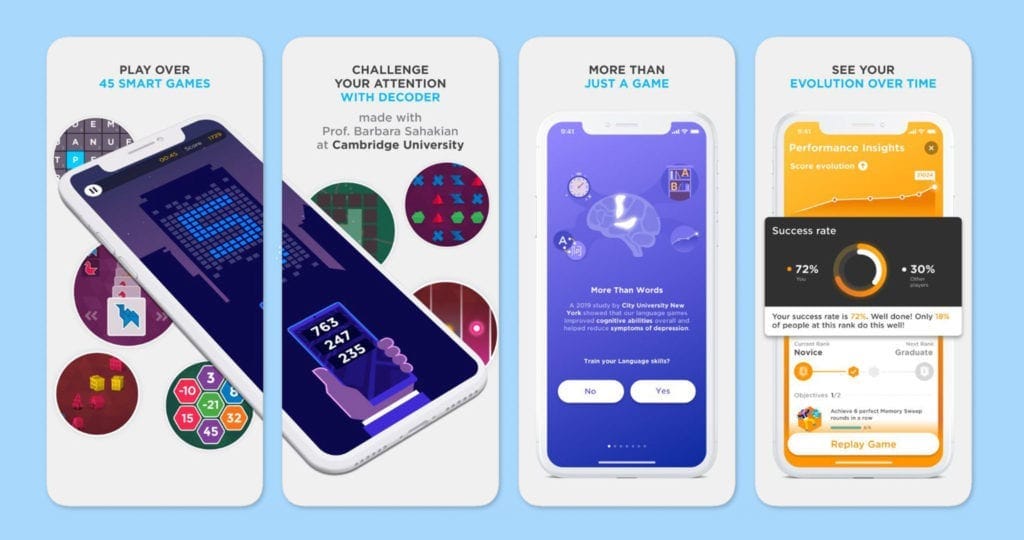

For example, a “brain training” app like Peak is popular because users enjoy the intellectual challenge of solving complex problems, making this an intrinsic incentive.Extrinsic Incentives: These are the external rewards that individuals receive from an activity. They are often financial, but they can also be non-financial. Extrinsic incentives are often used to motivate people who don't find the task itself rewarding.

For example, the achievement badges, leaderboards, challenges, reminders & goals of the Fitbit health tracking app would be extrinsic for most users, as they don’t particularly enjoy the hard work of staying or getting fit!If Fitbit failed to understand the fact that users needed extrinsic motivation, it would be easy for them to ignore these features - likely leading to product failure.

Conclusion

You can leverage incentives to boost a specific key metric (such as a referral programme increasing acquisition) or you see incentives as part of your core product strategy (such as the power of gamification in driving Duolingo’s high usage, retention & conversion to paid users).

Whichever approach - or combination of these approaches - will really depend on what product strategy you think makes sense for your product at this specific point in time.

The one thing you can’t do?

Ignore incentives.

It’s just too easy - and all too common - to end up creating unintended behaviour (remember the Cobra Effect) when you don’t stop to question your decisions.